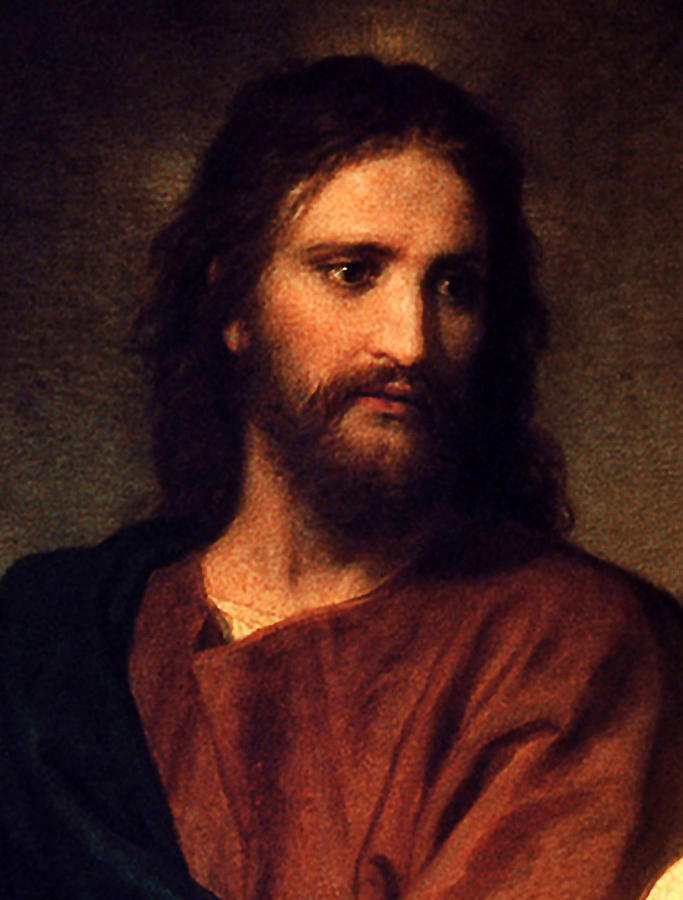

Questions 3 - Who Do You Say I Am?"

1 Introduction

One day Jesus and his disciples were entering Caesarea

Philippi. Jesus asks his disciples a question; “Who do people say the Son of

Man is?” They answer “Some say John the

Baptist; others say Elijah; and still others, Jeremiah or one of the prophets.”

The variety and uncertainty (“some say”) may suggest that it is the disciples

themselves who are still unsure of how to answer, not so much what the people

are saying. The first question sets the scene, though, for the next, more personal

and very direct question. In fact, this is arguably the most important question

of all time.

“But what about you?” he asked. “Who do you say

I am?”

Simon Peter jumps in with confidence;

“You are the Messiah, the Son of the living

God.”

As we read this passage we too are confronted with this same

question, and it is the topic for our discussion today. “Who do you say I am?”

2 Who

is Jesus Christ?

It

is helpful if we use some shared terms when answering this question. To start

with, the term “Word” or “Logos” is

used to name the second person of the Trinity. When this term is used we are

discussing the Divine nature of Jesus Christ.

Next

the term “Jesus of Nazareth” is used to name that human being who was born in

Bethlehem, walked the lanes and streets of Galilee, ate and drank with friends

and died on a Roman cross outside of Jerusalem around 2000 years ago. This

terms is used to discuss the human nature of Jesus Christ. The

relationship between these two “natures” has been a topic of intense debate, particularly

in the late third and into the fourth centuries A.D.

Some

suggested that Jesus was only Divine.

That is, what people saw when they looked upon Jesus was not really a human

being at all, but rather a ghost or phantom of sorts. This suggestion stemmed

from a foundational belief that created matter was evil. If this is the case

then how could the God of the universe unite himself to it? Rather, these

people suggested that Jesus only appeared

as a male human so as to save humanity from creation itself (the cause of

evil in the world). This view was refuted strongly and is considered a heresy.

Others

suggested that Jesus was only Human.

That is, all that people saw was a human man, nothing more, nothing less. There

is no relationship here between the Divine Logos

and the human Jesus of Nazareth. Rather, Jesus was just a human being who lived

a good life, showed us how to live as well, and died on a cross outside

Jerusalem. Again, this was strongly refuted and is considered a heresy.

On

top of this, the relationship between the second person of the Trinity, the Logos, and God the Father was also a

topic of intense debate. Was the Logos

“created” by God the Father? If so, then he is to be considered a lesser being.

Such a belief creates a hierarchy within the Trinity. This becomes problematic

when we consider the work of Jesus

Christ and the effectiveness of that work for salvation. If the Logos is not

“created” (as the Father is not created) then how are we to understand the

relationship between the persons of the Trinity? Here the term “begotten” was

used in distinction from “created” in order to avoid a hierarchy within the

Trinity, but preserve distinction between the persons of the Trinity. In a

similar way, the term “proceeded” was used in reference to the Holy Spirit.

There

are many other variations on these debates and it can be easy to sit in our

detached position 1600 years later and breathe a sigh of relief that we don’t

have to worry about these things. It is important to remember, though, that

what was considered “orthodox” was not yet formally defined. In fact, it was as

a result of these debates that “orthodox” belief was indeed defined.

Furthermore, orthodoxy is not just a matter of believing the right things, it

impacts the way we worship too, since orthodoxy comes from ortho – right, doxa –

glory. For example, if we believe that Jesus was only a human, then he is not

worthy of worship.

In

addition to this it is worth noting that the distinction between heresy and

orthodoxy on many occasions was only a very minor distinction (sometimes just

one letter!), but as with most debates each party prefers to distance itself

from the other so as to avoid being “tarred with the same heretical brush”.

3 The

Creeds

Creedal statements have always formed a part of the

Christian church. Indeed the earliest known Christian creed was simply “Jesus

is Lord” (Romans 10:9; 1 Corinthians 12:3). Over time, though, and in light of

some of the debates named above, these creeds were developed in order to

outline and affirm orthodox Christian belief. Whilst there were have been many

councils, synods and the like throughout church history, each with their own

kind of creedal outcome, there are three highly significant creeds that impact

our discussion today. The Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed and the Creed of

Chalcedon.

3.1

The Apostles’ Creed

The Apostles’ creed reads as follows

I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of

heaven and earth.

And in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord; who

was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under

Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead, and buried; he descended into hell; the

third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and sitteth on

the right hand of God the Father Almighty; from thence he shall come to judge

the quick and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Ghost; the holy catholic

Church; the communion of saints; the forgiveness of sins; the resurrection of

the body; and the life everlasting. AMEN.

Whilst Trinitarian in shape, much of the attention of this

creed is upon Jesus Christ. Even then, the attention is drawn to the death,

burial and resurrection of Jesus, with only a comma used to contain all that

existed in his life and ministry between his birth and suffering on the cross!

3.2

The Nicene Creed

Arguably the most significant and important of all Christian

creeds, it reads as follows

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker

of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten

Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of

Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with

the Father, by whom all things were made.

Who, for us men for our salvation, came down

from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was

made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and

was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and

ascended into heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father; and He shall

come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall

have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and

Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father [and the Son]; who with the Father

and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets.

And I believe one holy catholic and apostolic

Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the

resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Once again, as a result of the nature of the debates taking

place at the time of the Council of Nicaea (325A.D.) the focus of this creed is

upon Jesus Christ, seeking to define who he is and what he has done.

3.3

The Creed of Chalcedon

The Creed of Chalcedon (451A.D.) reads as follows

We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with

one consent, teach men to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ,

the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly

man, of a reasonable [rational] soul and body; consubstantial [co-essential]

with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according

to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all

ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us

and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, according to

the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only begotten, to be

acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly,

inseparably; the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the

union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring

in one Person and one Subsistence, not parted or divided into two persons, but

one and the same Son, and only begotten, God the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ;

as the prophets from the beginning [have declared] concerning Him, and the Lord

Jesus Christ Himself has taught us, and the Creed of the holy Fathers has

handed down to us.

There is no doubt that the focus of this creed is solely

upon Jesus Christ. What is significant in this last creed is that whilst it

clearly defines that Jesus is both fully human and fully Divine, it is still a

very inclusive creed since it does not specify how this relationship is to be

understood. As a result, a number of Christological models are permissible as

long as they affirm what is essential; that is, that there are two natures in

Jesus Christ, one human and one Divine, but both natures are permanently united

within his incarnated self. This is known as the “hypostatic union”. We affirm

this belief amongst our own creedal statements. Most specifically in our fourth

Article of Faith:

There is no doubt that the focus of this creed is solely

upon Jesus Christ. What is significant in this last creed is that whilst it

clearly defines that Jesus is both fully human and fully Divine, it is still a

very inclusive creed since it does not specify how this relationship is to be

understood. As a result, a number of Christological models are permissible as

long as they affirm what is essential; that is, that there are two natures in

Jesus Christ, one human and one Divine, but both natures are permanently united

within his incarnated self. This is known as the “hypostatic union”. We affirm

this belief amongst our own creedal statements. Most specifically in our fourth

Article of Faith:

We believe that in the person of Jesus Christ

the Divine and human natures are united so that he is truly and property God

and truly and properly man

The importance of the hypostatic union within Jesus Christ

cannot be understated and is to where our attention turns now. We will assume

this Chalcedonian Christology (summarised in our fourth doctrine) from hereon

for the purpose of simplicity and focus.

4 The

Hypostatic Union

Chalcedonian Christology has important implications for how

we interpret the person of Jesus Christ, his death on the cross, and his

ongoing mediatorial work for us now that he has ascended to the right hand of

the Father.

4.1

The Person of Jesus Christ

Chalcedon affirms that Jesus is fully human and at the same

time fully Divine. It is an incredible thought when we think of the moment when

the Holy Spirit came upon Mary, and within her womb began the formation of a

real human being with Divine origins. That moment in time is the very moment

when God (Logos) assumed humanity in

an inseparable, eternal and unchangeable bond.

Consider, though, that when the God of the universe united himself with

the very creation he had created by assuming human form was, for a brief moment

in time, no bigger than a single celled organism.

In Luke’s gospel we read that the child Jesus “grew and

became strong; he was filled with wisdom, and the grace of God was on him”

(Luke 2:40). The word “grew” may seem to be a minor detail but it is

significant that Jesus assumed the full meaning of what it means to be human;

from the womb to the tomb. If he had somehow just “appeared” as an adult male

and died on a cross then he would not have been “truly and properly man”. There

is something important about considering the fact that Jesus would have tripped

and skinned his knee as a boy, learned the skill of a trade from his father,

and even considering that he needed to be toilet trained. This is not meant to

be crass, but if we suggest otherwise then he was never truly human. He truly

entered fully into what it means to be human and experienced all that this

means, except for one thing – he did not sin.

4.2

His death on the cross

Paul, in Philippians 2, uses what appears to be an early

Christian hymn to describe the work of Jesus Christ. A significant word in this

hymn is the one translated “being” in the NIV. It is a difficult word to

capture fully and so other translations have also used the word “although”

here. Another alternative English word that could be used to translate this

term is “because.” This word expresses something very important in regards to

Jesus Christ.

If we use the word “because” here instead of “being” then we

see that it is not that Jesus acts “out of character” when as God he becomes

human and enters into every aspect of what it means to be human (“although” he

was God”). Rather, he acts “in character” when as God he becomes human and

enters into every aspect of what it means to be human (“because” he was God).

In reality what we are seeing when we look at Jesus Christ, his life, ministry,

suffering, and death, is not just him entering into the fullest experience of

humanity, but also the fullest display of exactly what God is like. As Jesus

“makes himself nothing” and “takes on the very nature of a servant” and

“humbles himself by becoming obedient to death” he is showing us the full

extent of who he is.

Jesus Christ shows us what true Divinity looks like.

Jesus Christ shows us what true humanity looks like.

This is who Jesus is and both natures are perfectly

displayed in his life.

4.3

The Great High Priest

The writer of the book of Hebrews goes to great lengths to

emphasise the ongoing Priestly ministry of Christ. Importantly, for the writer

of Hebrews, Jesus is both the sacrifice

(e.g. 10:10) and the Priest (e.g.

9:11) who offers that sacrifice. In

the temple the Priest slaughters a lamb, takes its blood into the Most Holy

Place, sprinkles it on the mercy seat in place of the blood of the people, then

returns to the people with the word of forgiveness from God. This is a

mediatorial role; this is the function of the priest. To act on behalf of both

the people and of God. This is exactly what Jesus Christ does, and because he

is truly and properly human and truly and properly God his perfect performance

of his function means that it is effective once and for all.

So, now that he has ascended into heaven, the first

resurrected human to do so, and is sitting at the right hand of the Father, he

continues to perform this priestly function. He continues to offer on our

behalf his own blood in place of our own. Because of his blood forgiveness of

sins is given and so he continues to speak that word of forgiveness from God

the Father back to us today.

For me, this is the most significant consequence of a

Chalcedonian Christology that impacts our worship today. In the resurrected and

ascended Jesus Christ we have a real human being, familiar with temptation, but

one who overcame it. Familiar with suffering and death, but one who overcame

it. One who shed his blood for the forgiveness of sin in a once and for all

death, effective for even the vilest of sinners. That same person is the second

person of the Trinity, the Logos,

who, as God, when he speaks the words “you are forgiven” has “all authority in

heaven and earth” (Matthew 28:18) to be able to do so, and so his words are

true.

He therefore takes our feeble, imperfect, and flawed

worship, unites it with his own perfectly obedient worship, sanctifying and

cleansing it, presents it to the Father not in an earthly temple, but in the

very heart of heaven itself. He then returns to us and speaks, by his Spirit,

to our Spirit. Confirming and affirming that we are indeed forgiven, that we

are adopted children of God, and because of this we too can join with Simon

Peter and exclaim in answer to Jesus’ question;

“You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God” (Matthew 16:16)

Comments

Post a Comment